Between Solitude and Silence: Ingrid Dorner's Photographic Exploration of Emotion

Ingrid Dorner interviewed by Edoardo Schinco

Ingrid Dorner is a French photographer based in Munich, whose emotionally charged artworks revolve around inspiring solitude and intimate family life. Vintage cameras, darkroom experimentation, and refined artistic techniques elegantly intertwine to explore themes of memory, transformation, and fragility. Subtle references to Kafka and Camus, along with a profound interest in liminal states, infuse her work with a unique emotional resonance that runs throughout her artistic practice.

Hello Ingrid, we're really happy to have you with us today. Before we begin, could you introduce yourself to our audience? Who are you?

My name is Ingrid Dorner. I am 44 years old. I am French, but I have been living in Munich for 15 years with my husband and two daughters.

After starting my career in theater and stage direction, I left behind the costume to express myself through photography. It has now been about ten years since I started exploring analog photography and developing my works in my darkroom. Alone. Solitude is essential for me to stay connected to my inspiration and instinct.

I regularly buy increasingly older cameras, including large format cameras, with the pleasant feeling of giving them a new chance to see the world. I have a very playful and childlike relationship with photography.

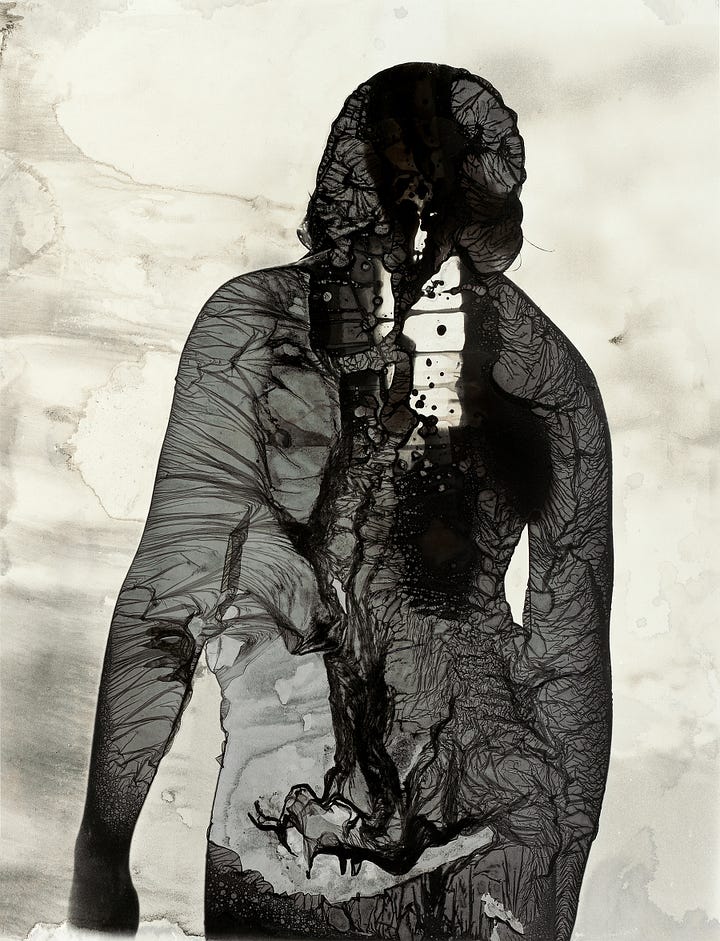

The moments of shooting are often simple moments of happiness in my life. These developed photographs, or negatives, become my treasures, my blank canvases, the starting point for a new experimental journey. I have explored nearly all experimental methods like Van Dyke, platinum palladium, and cyanotype, ultimately focusing on mordançage.

My work has been exhibited across Europe since 2018 and published in several magazines. I have received awards such as the first prize at the Passepartout Prize in Rome and was named “Photographer of the Year 2023”, winning the Annual Photography Award. This year, I participated in the Medium Photography Fair represented by Approche in Paris and at the Art Antwerp Fair [a contemporary fair in Bruxelles] with the In-Dependance gallery.

What does art represent to you? Is there a definition you prefer? And do you consider yourself an artist?

That’s a very complex question. It’s hard to reduce art to a single definition, but I like the idea that art is, above all, a subjective experience. I particularly appreciate definitions that emphasize the pure intention of the artist and the emotional impact the work can have on the viewer. For me, art is a powerful fluid of sincerity that materializes in an image, a sculpture, a piece of music...

As for whether I consider myself an artist, it’s always complicated to say so because it can seem pretentious. Let’s just say I feel deeply connected to my creative process, and I am passionate about the idea of transforming my thoughts and emotions into images.

When and why did you start taking photos? What was your starting point? Are there any works or artists who have inspired you throughout your journey?

I got my first film camera when I was 13. But for many years, it was theater and stage directing that fueled my life. It wasn’t until I turned 30, quite unexpectedly, that photography became a form of expression for me – this time behind the lens, in the darkness of my darkroom. This process offered me a new way to express myself. I wasn’t looking to put myself in the spotlight, but rather to capture moments, explore emotions, and convey my vision of the world.

One of the greatest sources of inspiration along this path was the birth of my first daughter. That powerful experience opened a door to the poetic expression of life, revealing the strength of fleeting moments and everyday joys. Photography became a way for me to celebrate those moments, to translate that deep awareness, and to share my fascination with the beauty and fragility of existence.

As for artists who might inspire me, I would, without hesitation, mention two writers: Franz Kafka and Albert Camus. Their worlds, balanced between reality and imagination, awaken my own imagination. Even though my work is very instinctive, the philosophy of Henri Bergson and Gaston Bachelard on temporality also nourishes my artistic approach.

How would you describe the artistic photography scene in France? Do you think there are connections between your work and the French artistic context?

The artistic photography scene in France is extremely dynamic and diverse, with a rich legacy of innovative artists and influential institutions. There’s a wide variety of styles, approaches, and themes that reflect the complexity of contemporary society. However, my work is not connected to this context.

The most difficult part of creating each of my pieces is precisely to never stray from my intimate path. I’m aware that many artists need to attend exhibitions and museums, to engage with as many other artists as possible in order to nourish and inspire their work. It’s a process I respect and find entirely valid. However, I need the exact opposite in order to create my most sincere and powerful images. I need to immerse myself in a kind of solitary purity, free of any influence, except for the love of my family. I do not denounce anything, except life itself through each of my images.

Can you tell me more about Franz Kafka and Albert Camus? How do they relate to your work?

I particularly love Kafka’s writing because it’s instinctive. His words paint a universe rather than simply telling a story. There’s a pictorial dimension to his writing that fascinates me – you don’t just read Kafka, you get absorbed by him, you enter into a substance, an atmosphere, a strangeness that never quite leaves you.

Camus, on the other hand, has this way of leaving a mark on the mind through imagery. Even if one forgets the storyline, what remains are flashes, sensations: the light of a moment, a silhouette on a beach, overwhelming heat, a silence. It’s those visual imprints that interest me in my own relationship with art.

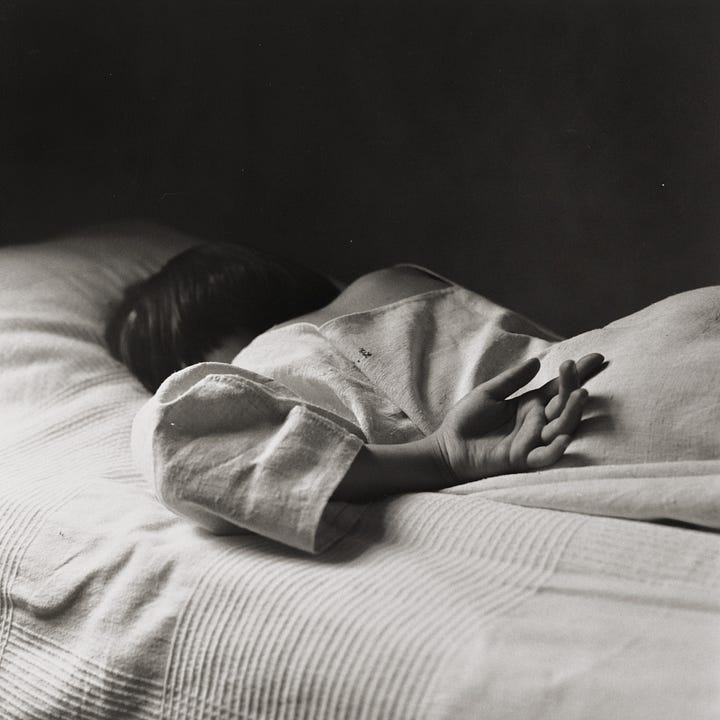

I would like my images to be perceived in that way—as reminiscences, fragments of memory that one carries without always knowing why.

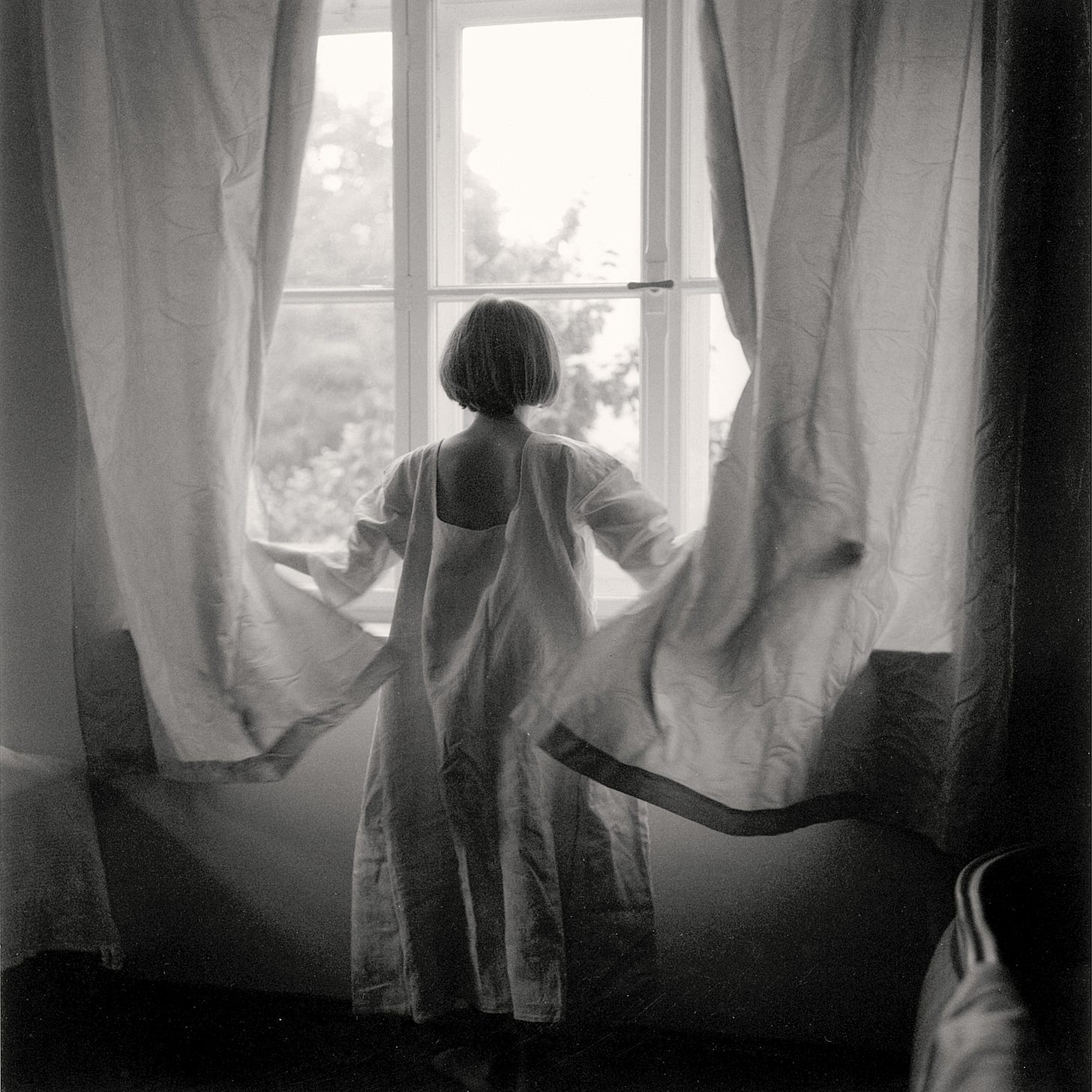

That’s precisely what I aimed to do with Zimmer 23: to create images that remain like fragments of an unwritten novel, a book of which only the scent of a memory lingers. Like those moments in life where we don’t necessarily remember the details, but which persist in us through a color, a shadow, a feeling of déjà vu.

What is your view of artistic creativity and its connection to your need for solitude?

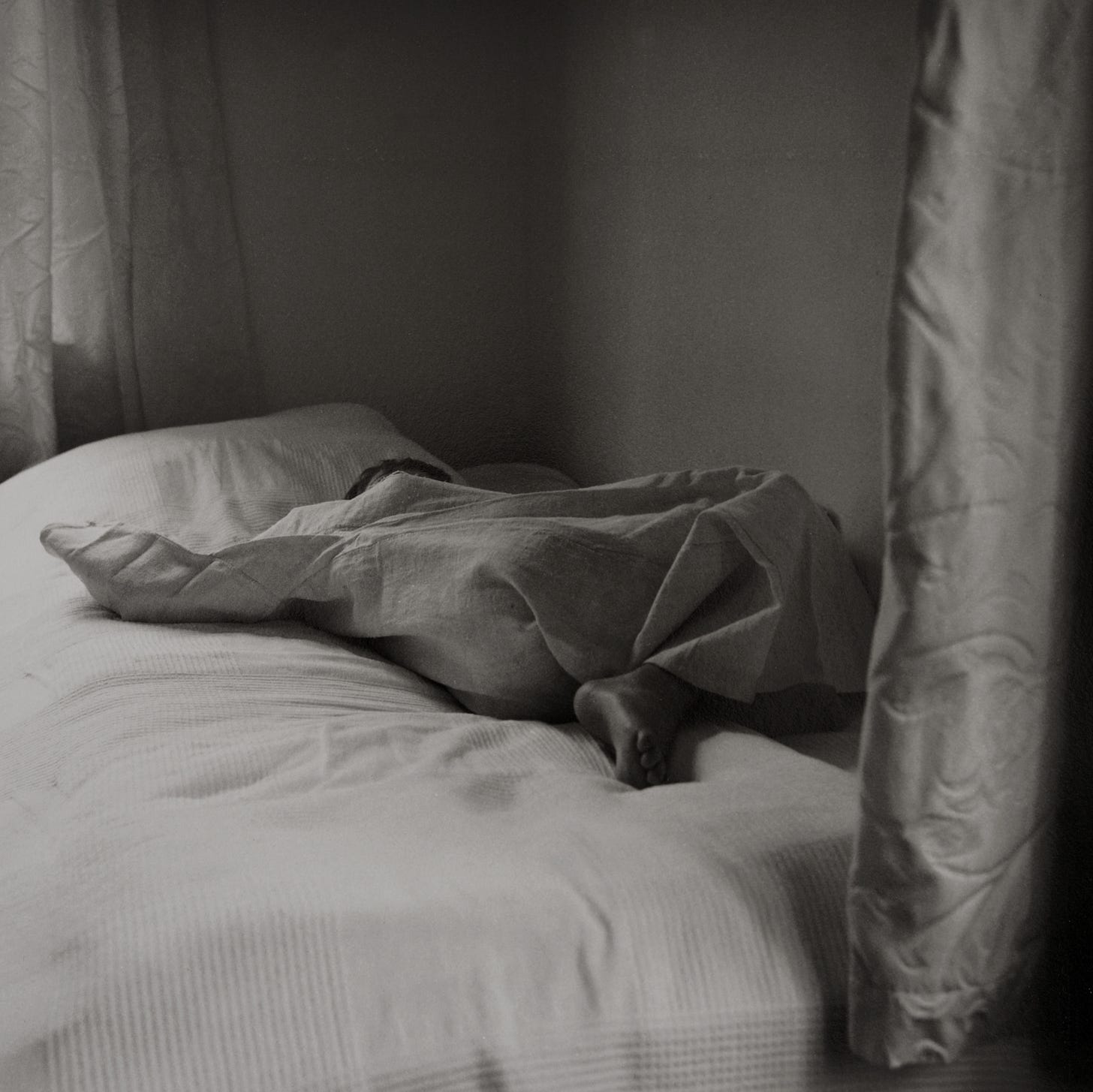

My view of artistic creation is intimately tied to a state of transition, an in-between, an uncertain territory where things are neither fixed nor fully defined. That’s what led me to explore the concept of the Liminal – this intermediate space where everything is suspended, in transformation. I see the creative act as a shift between multiple realities, between the intimate and the universal, between memory and reinterpretation.

For me, creating is about navigating that blurry space, where the image isn’t just a representation of reality but becomes a resonance, an echo of an emotion, a fleeting sensation. It’s not a rational or premeditated process. I don’t aim to tell a linear story, but rather to capture fragments of memory, impressions that linger without us knowing exactly why.

With Liminal, I wanted to give form to that transitional state – that sensation of being on the edge of something, without being able to name it clearly. These are images that function as thresholds: they don’t offer answers, they open doors to buried memories, to drifting states of mind.

But this series, like my work in general, evolves with my life. When I began Liminal, it reflected a personal state of drifting—a meditation on memory and imagination. Today, the series has taken on a new dimension, influenced by an experience that deeply shook my existence: my daughter’s leukemia. I was thrown into another form of Liminal, a time suspended between illness and healing, a space where every moment wavers between hope and uncertainty.

Chemotherapy is a strange, terrifying, and fascinating process all at once – it’s chemistry that destroys in order to rebuild, a fragile balance between destruction and repair. That duality resonates with my artistic approach, where I manipulate my images, sometimes mistreat them, immerse them in chemical baths to transform them and give them new life.

This parallel between analog photography and medicine became strikingly clear to me.

From this realization, the idea for a future project was born: a photographic book in homage to science, to medicine, to researchers. This project will be a testimony, a gesture of gratitude toward those who work in the shadows to make the impossible possible.

Ultimately, Liminal is more than a series – it’s a reflection on transformation, on those moments when we shift from one state to another. It’s a series that grows with me, with my story, and that now carries within it this experience of struggle and hope.

As for solitude, I don’t really seek it – it imposes itself on me. It’s not a deliberate choice, but an absolute necessity. As soon as there’s any kind of contact, I lose that essential introspection that allows me to create. My work relies on a fragile inner dialogue, on sensations that emerge and vanish in silence. External interference breaks that process. I need that isolation – not as a rejection of the world, but as a way to better translate it.